By Tom Clynes

Author’s Note: After a half-year of brainstorming about National Geographic Magazine’s yearlong celebration of America’s national parks, the magazine’s editors offered me the pick of the litter.

The choice was easy. Denali National Park, the crown jewel of America’s park system, offered a range of possibilities broad enough to be a world unto itself. It also offered some formidable challenges. I quickly realized that the normal conventions of outdoor reporting wouldn’t cut it in this vast wilderness, which is cut by only one 92-mile-long road.

I would spend a total of five weeks walking, skiing, flying and dog-sledding through the park’s spectacular terrain, during the extremes of the Alaskan winter and summer. These explorations yielded enough stories and images and controversies to fill dozens notebooks and photo data cards.

In the end, only a small fraction of this material fit into NatGeo’s 28-page feature, leaving plenty of adventures to share for the first time with audiences at my upcoming talks and presentations.

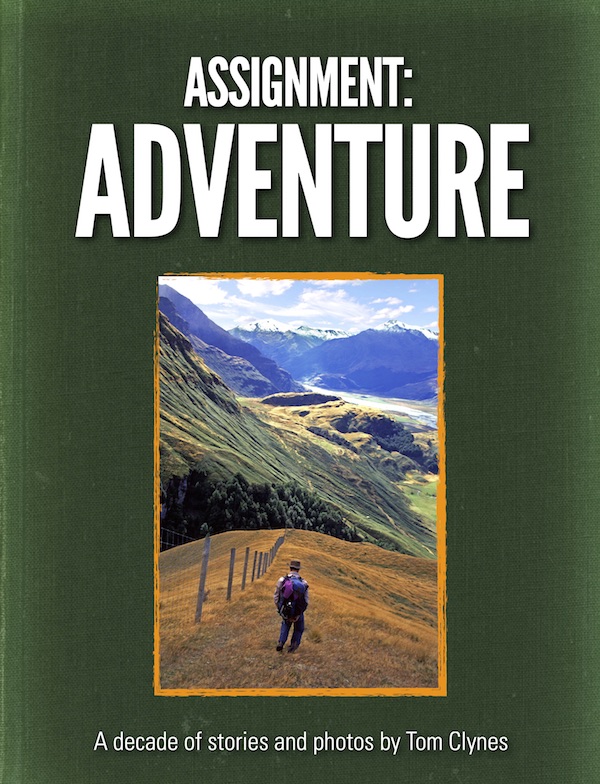

Denali: The icon of Alaska’s wilderness symbolizes the tension between preservation and use at U.S. national parks.

PARK RANGERS here call the high season—from June through early September, when Denali National Park and Preserve hosts the majority of its 500,000 annual visitors—the “hundred days of chaos.” Indeed a midsummer morning at the park’s Wilderness Access Center, located at the start of Denali’s fabled 92-mile-long Park Road, can feel a bit like rush hour at Manhattan’s Port Authority Bus Terminal. Loudspeakers announce bus boarding times, and visitors from many nations crowd the ticket counter.

Most of Denali’s visitors are cruise ship passengers who see the park and its prolific wildlife largely through bus windows. “But if you’re seeking solitude, it’s not hard to find,” says ranger Sarah Hayes, who helps backpackers and hikers prepare for their adventures. “We’ve got six million acres of mostly trailless lands where wild animals roam undisturbed. And it’s accessible to anyone who hops off the bus.”

As my bus rolls out, noses press against windows, hands clutch cameras, and people speaking half a dozen different tongues excitedly speculate about wildlife sightings. I ask several passengers what’s on their wish list. “A moose!” “A grizzly!” “Caribou!” “A wolf!”

At the five-mile mark we spot our first animal. “Squirrel!” a kid yells, bringing the bus to laughter. After the 15-mile mark, the road turns to dirt and empties of cars. A few miles farther along the trees disappear. As the distant peaks of the Alaska Range come into view, the scale of this kingdom of nature becomes apparent. The driver slows down.

“It’s been hiding for two weeks now,” he says, wheeling the vehicle through a tight turn. “But there’s a pretty good chance that today …” As the towering mountain comes into hazy view, a dozen voices sing out, “Denali!”

Rising 20,310 feet above sea level, North America’s tallest peak is a stunning sight, although in warm weather its slopes are often shrouded in clouds. The mountain was a big part of the legend and lore of the Athabaskan-speaking people who gave it the name Denali, meaning Tall One. In 1896 gold prospector William Dickey renamed it Mount McKinley in honor of Ohio politician William McKinley, a staunch champion of the gold standard who one year later would become the nation’s 25th president. For decades Ohio’s congressional delegation successfully blocked attempts to rename the mountain. Then last summer the Obama Administration used its executive power to restore the original name.

Seeing the mountain, spotting a grizzly, or catching a glimpse of a wolf are the top three reasons people give for coming to Denali. As recently as 2010, a visitor stood a better chance of seeing a wolf in the wild than seeing the elusive Tall One, which is visible on just one in three summer days. But since 2010 the number of wolf sightings has plunged. According to a study of wildlife viewing opportunities along the Park Road, observers recorded wolf sightings on only 6 percent of trips in 2014—down from 45 percent in 2010. Park biologists report that the number of wolves inside the park has dropped from more than 100 a decade ago to fewer than 50 last year. I came to Denali, in part, to discover why.

Author, photojournalist and keynote adventure speaker Tom Clynes travels the world covering the adventurous sides of science, the environment and education. His work appears in publications such as National Geographic, The New York Times, Nature, Popular Science, and The Atlantic. As a keynote speaker, Tom inspires audiences and brings them along “on assignment” to fascinating locations around the globe. Whether your group or organization is in search of adventure speakers, environmental speakers or your own in-house “National Geographic speaker series,” Tom’s presentations will earn high praise. To contact Tom and find out more about his memorable and inspiring programs, email info[at]tomclynes.com.